What ventilation is really doing

Ventilation changes pressure and flow paths. That redistributes heat, smoke, and toxic gases, and it fuels or starves the fire depending on what you open, when you open it, and what water you’ve already put on the fire. UL FSRI studies show additional openings create new flow paths that can rapidly accelerate conditions if not coordinated with suppression. Bottom line: if you add air without controlling the outlet and the fire, you may make it worse.

When UK doctrine guides the tactic

- National Operational Guidance (NFCC) sets out good-practice principles you tailor locally use it to frame your risk assessment, hazard identification, and control measures before choosing a ventilation mode.

- JESIP’s Joint Decision Model (JDM) gives you a shared picture across Fire, Police, and Ambulance, and a repeatable way to test your ventilation plan against operational priorities and risks (and to log those decisions).

- Approved Document B (ADB) and BS 9991:2024 reshape what you’ll meet on the fireground sprinklers, second stair requirements, residential smoke-control strategies, and firefighting shafts that influence your vent choices and exhaust routes.

The four core modes (and when to use them)

- Natural (horizontal) ventilation

Openings at the same level (windows/doors) to move smoke across and out. Best when the fire is controlled, the outlet is upwind and above the fire area, and you can confine air intake. Misplaced second openings can create a stronger flow path past unburned rooms. - Vertical ventilation

High-level outlets (roof hatches, AOVs, natural vents) to lift heat and products of combustion. On pitched roofs or wind-influenced fronts, a new top opening can draw the fire toward crews; coordinate with water on the seat and ensure a single, known exhaust. - Positive Pressure Ventilation (PPV/PPVf)

A fan at the entry creates slight over-pressure to push smoke toward a controlled exhaust. It’s powerful for visibility and temperature but only if the outlet is defined, the fire is controlled or being controlled, and crews are briefed on the flow direction. - Smoke-control systems (mechanical or natural)

In modern UK buildings you’ll encounter designed systems stair/lobby pressurisation, corridor extraction, firefighting shafts with vent provisions. Use them as intended; don’t defeat a pressurised stair with an open door unless commanded and coordinated.

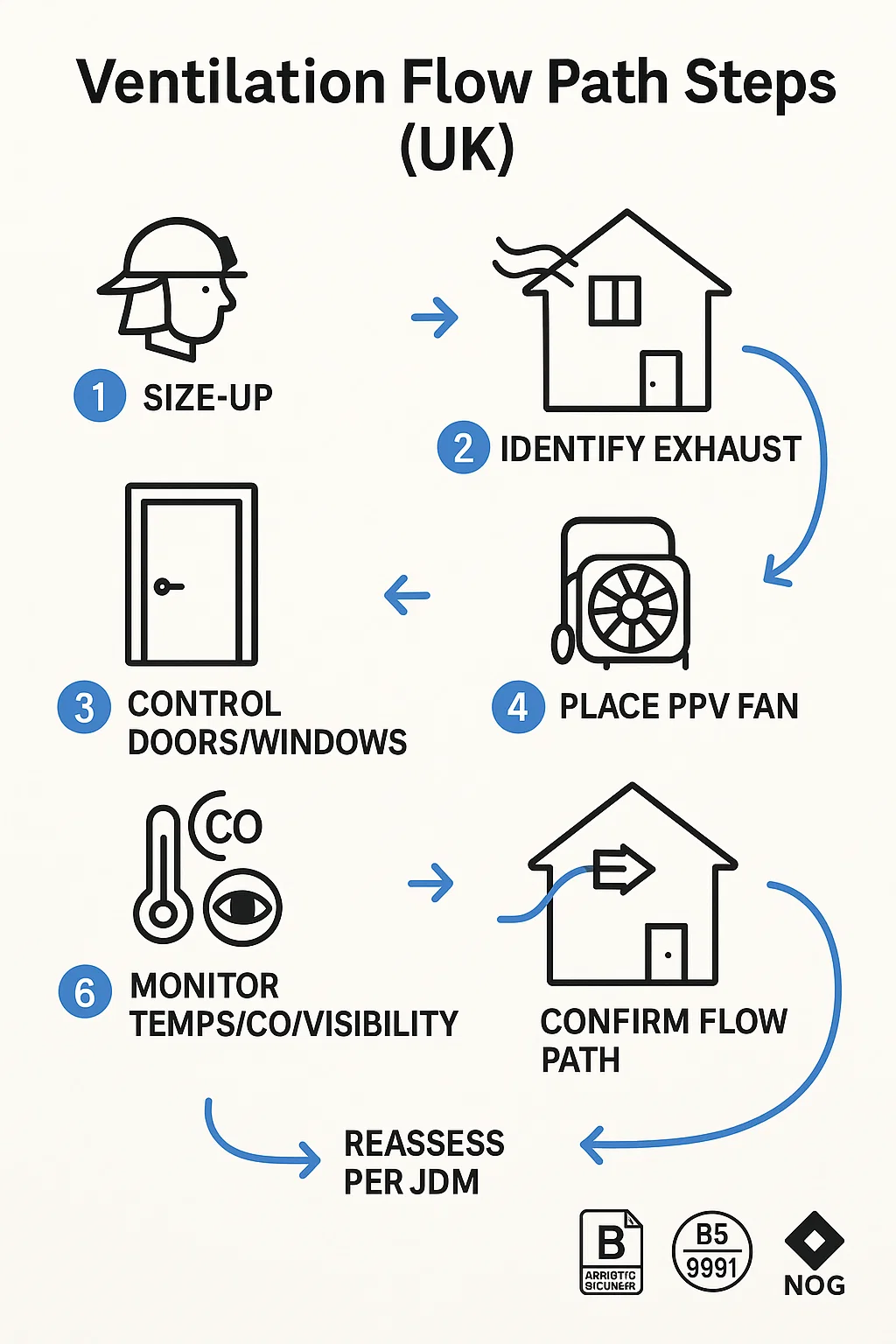

Step-by-step: the UK ventilation sequence

1) Build the shared picture

- Confirm incident priorities, hazards, and resources through JDM. Record rationale and the risk to responders/occupants.

2) Stabilise the fire

- Apply water to the seat or compartment door (pulses/short bursts) to drop the energy before big openings. Ventilation supports suppression, not the other way round.

3) Choose the flow path

- Select one exhaust and one intake. The exhaust should be closer to the fire than uninvolved rooms and, ideally, higher. Keep all other potential openings controlled.

4) Control doors

- Door control at the entry is a tactic, not an afterthought: crack, assess, and coordinate with BA movement and the fan if using PPV.

5) Execute the mode

- Natural/vertical: open exhaust first, then create the inlet.

- PPV: place fan, confirm seal at the doorway, open exhaust, then power up.

- Smoke-control: enable the designed system for that zone; liaise with responsible person/BMS if available.

6) Monitor and adapt

- Watch temps, visibility, CO/CO₂ where monitored, and fire behaviour. If conditions worsen, shut down the new opening, reinforce suppression, and reset. Log changes under JDM.

PPV in practice: placement, pressure, proof

- Placement: Fan cone must cover the full door; adjust distance until the “air curtain” seals the opening.

- Pressure: You’re not inflating a building just enough differential to move smoke. More CFM isn’t always better if exhaust is small or interior doors are open.

- Proof: The proof of PPV is in the corridor temperature drops, visibility improves, and smoke movement favours your chosen route. If it doesn’t, you haven’t built a coherent flow path.

Quick reference table PPV setup by context

| Context | Preferred Exhaust | Intake Control | PPV Notes | Watch-outs |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2-storey dwelling, fire in rear lounge | Rear window in fire room | Front door with fan seal | Start after water on seat/ceiling | Second opening on first floor may steal flow path |

| Mid-rise corridor fire (residential) | Corridor end AOV/extract | Lobby door controlled | Confirm system status; coordinate with shafts | Don’t depressurise protected stair |

| High-rise flat fire, stair pressurised | Balcony/window of fire flat | Door with doorman + fan | Keep stair doors closed; manage lobby pressure | Opens to corridor can defeat pressurisation |

| Retail unit on windward frontage | Lee-side rear door/window | Wind-side door with fan | Wind can invert flow test before committing | Wind-driven fire conditions escalate fast |

Use local SOPs and building systems as the first reference in real time.

Flow-path control: small choices, big consequences

Every new hole is a decision. FSRI’s comparative animations show that limiting extra openings keeps the flow path predictable and reduces rapid fire spread. In UK dwellings, that may mean keeping first-floor windows shut until the fire room exhaust is established. In taller buildings, it often means preserving stair pressurisation and using the designed smoke-control route as your exhaust.

Wind-driven and low-intake/high-exhaust scenarios

When wind or stack effect pulls smoke hard toward a higher outlet, a small inlet and a big exhaust can supercharge conditions between the two. UL FSRI training released in 2025 emphasises recognising “low-intake/high-exhaust” setups and changing the geometry reduce exhaust, relocate intake, or shut down the opening while water cools the seat.

Designed smoke control in UK buildings

ADB and BS 9991/BS 9999 embed smoke-control expectations: automatic opening vents (AOVs), corridor extract, pressurised stairs, and defined firefighting shafts. Your job is to use those systems as intended and avoid defeating them accidentally. If the stair is pressurised, preserve door discipline. If the corridor has extract, make that your exhaust before spinning up PPV. Coordinate with the responsible person/BMS to verify status and overrides.

Command and logging that hold up after the debrief

JESIP’s Joint Doctrine makes this simple: use the JDM to capture the ventilation plan, the trigger to start, the metric to continue (visibility/temperature trend), and the red lines to stop. Note who authorised enabling or overriding any smoke-control system, and the time you switched modes. Good logs explain good outcomes and defend decisions if the plan had to change fast.

Step-by-step checklist crews can run on

- Establish JDM: priorities, risks, resources, and what success looks like.

- Water first: cool the compartment or keep it contained at the door.

- Pick one exhaust, pick one intake; brief the route of smoke.

- Control the door; manage BA entry with the plan.

- Natural/vertical: open exhaust, then inlet. PPV: set fan, then create/confirm exhaust.

- Use building systems as designed; protect pressurised stairs.

- Monitor: temps, visibility, gas readings where used; adjust or abort if conditions worsen.

- Log the decision changes and timings (who/what/why).

Pro Tip #1

If visibility isn’t improving within 60–90 seconds of PPV, you probably don’t have a sealed entry or a viable exhaust. Shut the fan, reset the flow path, and re-confirm water on the seat before trying again.

Pro Tip #2

At high-rise incidents, assume the stair is your lifeline. Keep it pressurised and smoke-free. If a corridor door must be wedged for hose management, assign a firefighter to that door and coordinate openings to keep the pressure advantage.

Safety considerations you should brief out loud

- BA egress: Don’t push smoke toward your own escape route.

- Victim survivability: Venting a bedroom behind a closed door may turn a tenable space into an outlet.

- Coordination with Police/Ambulance: Communicate before you alter smoke travel that affects warm-zone positions. Use M/ETHANE updates as your “heads-up” for major ventilation changes.

Training reps that build real competence

- Run PPV drills with door control and a “rogue opening” injected by instructors crews must diagnose and correct the flow error.

- Include wind in your scenarios; simulate a strong leeward exhaust and practice reversing it.

- Walk new residential blocks with facilities teams to understand which vents are automatic, which are manual, and how the BMS presents status. Tie this back to ADB and BS 9991 updates so your mental model matches current buildings, not memory.

Frequent mistakes

- Opening “for a look.” That’s still ventilation. If you must look, do it with the door cracked and a plan.

- Two exhausts fighting each other. Pick one; shut the rest.

- Forgetting wind. If wind pushes in at your “exhaust,” it isn’t an exhaust anymore swap roles or relocate.

UK standards and guidance to keep in your pocket

- National Operational Guidance (NFCC): operational ventilation principles and risk controls.

- JESIP Joint Doctrine & JDM: shared picture, decision control, and logging.

- Approved Document B: statutory guidance shaping smoke control features you’ll meet.

- BS 9991:2024 / BS 9999: design-use codes for residential and other buildings that influence local SOPs.

- UL FSRI ventilation research: evidence base for flow-path and PPV timing.

Short scenario walk-throughs

1) Two-storey semi, fire in front room, wind on the street

Water on the seat through the front door while a rear window becomes the exhaust. PPV at the front only after rear exhaust is opened and confirmed. If wind overpowers your cone, consider rear intake/front exhaust reversal or shut down and go natural.

2) 8-storey residential, smoke in corridor, stair pressurised

Keep the stair doors shut. Use the corridor extract/AOV as exhaust, manage lobby door with a dedicated firefighter, and if PPV is chosen, place it to boost corridor movement toward the extract, not the stair. Log the control measures in the JDM.

3) Retail terrace, deep plan, limited rear access

Create a single front intake, cut a rear exhaust (or open an existing one) once water is working the seat. Keep internal doors shut to stop smoke marching into stockrooms. If the rear cannot be established, go defensive on ventilation and favour containment.

Debrief cues that actually improve the next one

- Where did the smoke actually go versus the plan?

- What was the first sign the tactic worked (or didn’t)? Temperature? Visibility? Gas reading?

- Which door caused you pain? How will you assign a human to it next time?

- Did we record the decision gates under JESIP? Would it read clearly to someone who wasn’t there?

FAQs

Is PPV safe before water is on the fire?

Not recommended. Evidence shows adding air without controlling the heat source can accelerate burning and push products of combustion along your egress. Prioritise cooling or confinement first.

What if the building has an AOV and pressurised stair?

Use them as intended don’t defeat the stair. Set your exhaust to the designed route and keep stair doors closed. Coordinate with facilities if overrides are needed.

How do I know ventilation is helping?

Visibility improves toward your outlet, heat reduces where crews work, and gas readings trend safer where monitored. If not, abort, reset the flow path, and reassess under JDM.

Who authorises venting a roof or overriding smoke control?

The incident commander, informed by the JDM, after confirming benefits outweigh risks and that suppression is coordinated. Record the decision, time, and person.

Does ADB 2025/2026 change my tactics?

It changes building features you’ll meet (sprinklers in care homes, wider smoke-control expectations, second stairs in some residential buildings). Your tactics adapt to those systems know them and use them.

Emma Lee, an expert in fire safety with years of firefighting and Rescuer experience, writes to educate on arescuer.com, sharing life-saving tips and insights.