Here’s what matters: Vancouver isn’t an easy place to run an incident. You get glass towers one block, 120-year-old brick structures the next, seawall traffic, cruise terminals, condo lobbies with six layers of access control, and streets so tight a single mis-parked truck can choke half your resources. That’s reality and ICS needs to flex around it, not the other way around.

If you’re the first-arriving officer, you don’t have time for theory. You need clean decisions, strong priorities, and a way to bring other agencies into the same picture without slowing down.

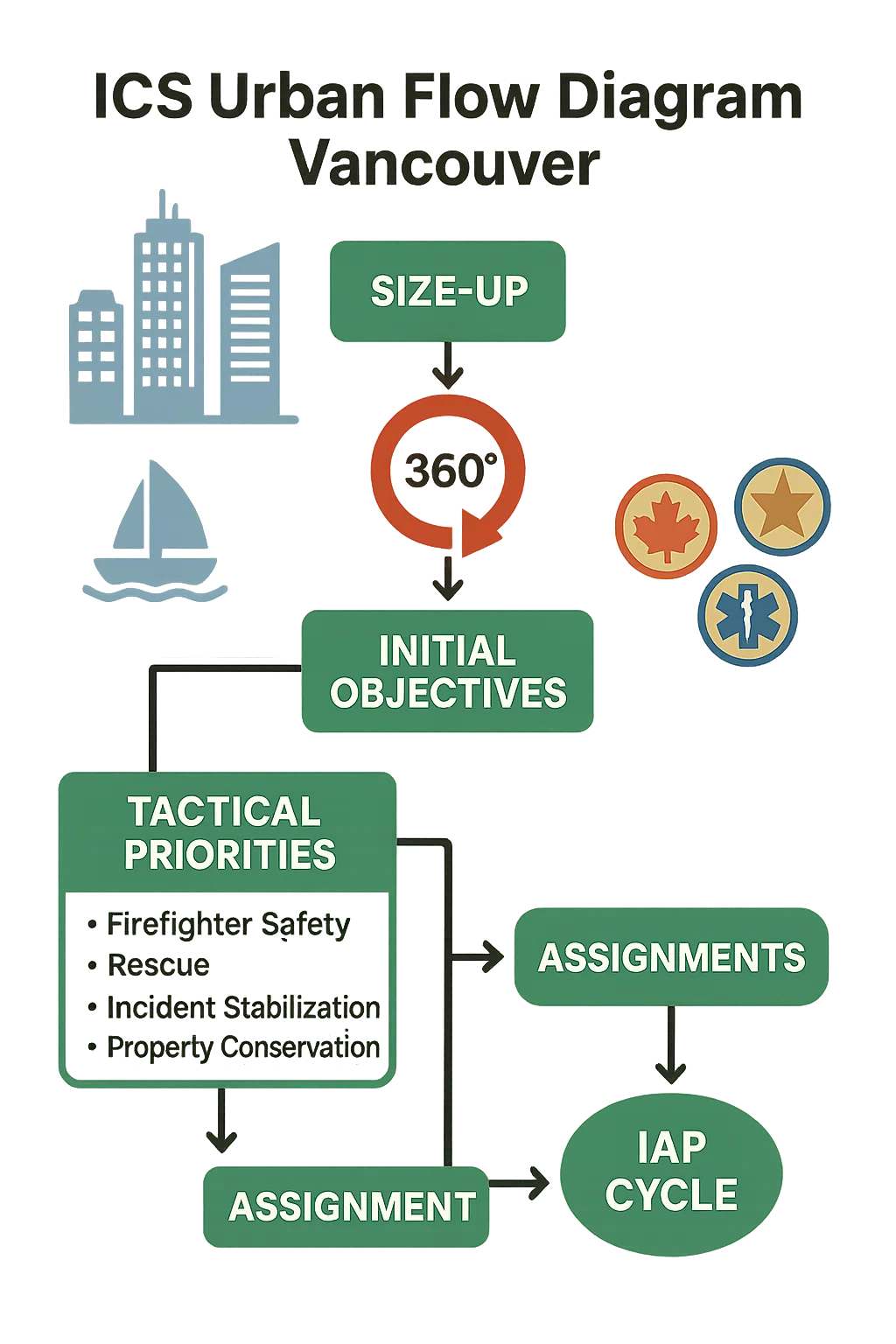

This playbook walks you through that chain: initial size-up → establishing command → tactical priorities → division/group carving → building your first IAP → keeping the cycle tight even as the incident gets messy. Think of it as a Vancouver-native version of ICS: grounded, fast, and honest about the way this city works.

Why Size-Up Shapes Everything That Comes Next

Every responder knows the truth: the first minute is where you either set the incident up for clean control or you create chaos for the next 40. Vancouver’s geography exaggerates this. You’re not just battling the fire or the medical emergency you’re navigating narrow lanes, mixed traffic, curious pedestrians, and buildings that love throwing surprises.

A strong size-up isn’t a script. It’s awareness, judgment, and priorities delivered in a way that helps every other agency plug into your plan.

You want your people to hear confidence on the radio because confidence reduces hesitation and hesitation kills time.

What a Vancouver-Ready Size-Up Sounds Like

Keep it natural. Keep it visual.

Example:

“Command to dispatch, we’re on scene at a 20-storey mixed-use tower, smoke visible from the 10th floor on the east side. Occupants self-evacuating into the lobby. No flame visible yet. Establishing Main Street Command on the Alpha side. Vancouver Police for traffic control, BCEHS for standby. Starting a 360.”

See the rhythm? Short. Purposeful. Real.

Now let’s break down the pieces you need.

Checklist Insert Size-Up Essentials for Vancouver

First-Arriving Officer Size-Up Checklist

- Building type (high-rise, mid-rise, heritage, mixed-use, industrial, marine-edge)

- Conditions (smoke/flame, visible hazards, structural concerns)

- Occupancy load and evacuation behaviour

- Access points (lobbies, loading bays, locked entrances)

- Traffic and lane control needs

- Water supply (hydrant direction, distance, obstructions)

- Exposure concerns (tight spacing between buildings, alleyways)

- Wind conditions from the harbour

- Immediate tactical priorities (rescue, fire attack, containment)

- Requesting additional alarms early

- Confirming command name and location

Nothing fancy just what you need to make informed moves fast.

Why Vancouver Demands a Stronger 360°

A complete 360 isn’t optional here. You’ve got alleys you can barely walk through, loading docks that double as hazards, and glass façades that behave unpredictably under heat. The back of a Vancouver building rarely matches the front.

You’re not chasing perfection; you’re chasing clarity. Even a partial 360 (if construction or hazards block you) gives you better tactical footing than guessing.

When You Establish Command, Your Voice Sets the Tone

Some officers talk like they’re reading a report. Vancouver incidents need something better: a command presence that’s direct without being dramatic.

The faster you claim command, the faster the rest of the world orients around it. Police know where to park. BCEHS knows where staging sits. Engineering services know where utilities need to be killed.

A solid first announcement anchors the entire flow.

Recommended format:

- Identify yourself

- Name the incident

- Locate the command post

- Set the initial strategy

- Request resources

Example:

“Main Street Command established on the Alpha side. Offensive strategy. Need Police for lane closure and BCEHS for standby. Lobby Group forming.”

Clean. Human. Clear.

NFPA Touchpoints

- NFPA 1561 ICS structure and command transfer

- NFPA 1700 Coordinated fire attack considerations

- NFPA 1021 Officer-level decision-making

- NFPA 1410 Initial attack drill principles

These aren’t citations for fluff they matter because Vancouver training often aligns with them.

Turning Size-Up Into Priorities: The Vancouver Pattern

Vancouver incidents follow a predictable pressure curve:

1. Life Safety

High-rise residents, tourists, commuters, construction workers.

Your first priority is protecting people not the building, not the timeline.

2. Containing the Hazard

Fire, chemical leak, medical surge, structural instability whatever it is, freeze it early.

3. Securing the Perimeter

This city crowds fast. Pedestrians love to get too close with phones out.

4. Stabilizing the Building or Scene

Think elevators, stairwell door integrity, mechanical rooms, rooftop units.

5. Working with the Other Agencies

Police, BCEHS, engineering, transit, marine units, security. Each one adds friction unless command syncs them early.

Table Insert Tactical Priorities by Incident Type

| Incident Type | First Priorities | Vancouver Notes |

|---|---|---|

| High-rise fire | Lobby control, fire floor recon, stairwell isolation | Access control systems slow you down. Assign Lobby early. |

| Marine-edge rescue | Scene safety, water-side lookouts, patient access | Tidal range changes working conditions by the minute. |

| Gas leak | Isolation, evacuation, ventilation | Many old buildings hide unmarked shutoffs. |

| Transit corridor incident | Lane control, triage, hazard zone set-up | Peak hours create instant secondary risks. |

| Downtown medical surge | Triage, BCEHS integration, pedestrian control | Crowded sidewalks complicate patient access. |

Building Divisions and Groups Without Overcomplicating the Scene

Here’s where ICS often loses people. They start drawing boxes instead of leading.

Divisions and groups aren’t decorations they’re how you cut the chaos into manageable lanes.

Vancouver’s most useful early assignments:

- Division 1 / Division Fire Floor

High-rise incidents need eyes and decisions on the right floor. - Lobby Group

This is non-negotiable. Key cards, elevators, fire control panels Lobby is the city’s friction point. - Staging Area Manager

Preferably one block out from the incident. - Medical Group

Always integrate BCEHS immediately. - Ventilation Group

Especially during high-wind days from the harbour.

The goal isn’t to build a tree; it’s to maintain clarity.

The First IAP: Fast, Simple, Flexible

Forget the idea that an IAP is a stack of documents. On the street, your first IAP is a handful of decisions that tell your people how the next 15–30 minutes will go.

A Vancouver-ready IAP answers five questions:

- What’s the problem right now?

- What’s the plan to freeze it?

- Who owns which piece of the plan?

- What resources do we need to do it?

- How will we track changing conditions?

You can write that on a board, speak it over the radio, or dictate it to a command aide.

What matters is clarity, not paperwork.

Sample Initial Vancouver IAP

Incident Goal: Stop vertical extension on the 9th floor.

Objectives:

- Fire Floor Team conducts recon and starts an interior attack.

- Lobby Group controls evacuation flow and elevators.

- Division 1 contains smoke migration.

- Medical Group stages BCEHS paramedics for potential rescues.

- Police hold the perimeter for apparatus access.

Operational Period: First 20 minutes.

Triggers for Plan Revision:

- Fire breaches into another floor

- Wind shifts affecting ventilation

- Additional evacuations needed

- Structural integrity concerns

No jargon. Just direction.

How You Keep Control When the Scene Grows

Vancouver scenes rarely shrink. Once command starts stacking in more resources, your mental bandwidth drops unless you offload fast.

When to assign a Safety Officer

Early the density and unpredictability of these buildings demand it. Look for falling glass, electrical hazards, and HVAC systems pushing smoke in weird directions.

When to create Unified Command

Any time BCEHS or Police share operational responsibility, which is common downtown.

Unified doesn’t mean “committee.” It means shared situational awareness.

When to add more divisions

The moment your radio traffic starts stepping on itself.

Pro Tip Box Don’t Let the Lobby Eat Your Incident

The lobby of a Vancouver tower is a world of its own: secure doors, multiple elevators, concierge, alarms, residents, construction workers, security staff.

If you don’t assign Lobby Group early, the lobby will derail your entire plan.

How You Keep the Incident From Fragmenting

Your crews need to know four things without delay:

- What’s happening

- What they’re supposed to do

- What’s changing

- What’s becoming unsafe

If communication breaks, ICS collapses.

Use short, natural radio transmissions. No reading off cards.

Your voice should feel like a guide, not a narrator.

Smoothing Multi-Agency Friction

Vancouver crews know the truth: the incident goes smoother when Police and BCEHS feel included early.

What works best:

- State the strategy and hazards in plain language.

- Tell BCEHS exactly where Medical Group wants them.

- Give Police a simple perimeter assignment, not a mystery.

- Bring building engineers into the loop if alarms or HVAC need manipulation.

You’re not doing diplomacy here you’re doing efficiency.

Pro Tip Box Bring BCEHS Into the Building Early

On high-rise fires, don’t leave paramedics at street level.

Smoke injuries, elevator problems, heat exhaustion they happen fast inside towers.

A forward BCEHS team integrated with Medical Group saves minutes you can’t afford to lose.

Sustaining the IAP When the Incident Keeps Fighting Back

Here’s where experienced ICs earn their keep.

The first IAP is easy. The second and third test your discipline.

Your IAP cycle needs three moves:

- Update conditions

- Update objectives based on those conditions

- Update assignments to match the objectives

That’s the engine of ICS.

The city changes fast your IAP has to change faster.

When You Transfer Command, Make It Count

Transfers in Vancouver often happen when the first-arriving officer hands off to a chief.

Don’t make them guess what you’ve built.

Your transfer should include:

- Current conditions

- Current objectives

- Current assignments

- Outstanding hazards

- Resources en route

- Divisions/groups and their progress

If the incoming IC understands your plan in one minute, you’ve done your job.

A Calm Close Matters More Than You Think

After the fire is out or the scene is stabilized, responders sometimes mentally check out. That’s where mistakes still happen moving equipment too fast, missing structural warnings, ignoring carbon monoxide buildup, or forgetting to do a headcount.

Vancouver post-incident must-haves:

- CO checks

- Accountability hard reset

- Decon if needed

- Elevator and system resets (with building engineers)

- Street reopening plan with Police

- BCEHS patient follow-up

- Command log finalization

It’s cleanup that protects the next team on the next call.

FAQs:

How do I simplify divisions in a high-rise incident?

Start with Fire Floor, Floor Above, Lobby, and Staging. Build outward only when radio traffic becomes congested.

When should I form Unified Command in Vancouver?

Any time Police or BCEHS share operational responsibility. Downtown and marine-edge calls trigger this often.

What makes Vancouver size-ups different from other cities?

Building diversity, coastal weather, vertical density, and access issues create more variables per square metre.

How detailed does the first IAP need to be?

Think clarity over length. A few solid objectives beat a page of vague intentions.

Do I always need a Safety Officer?

Almost always in Vancouver’s urban environment. Falling glass, old wiring, construction, and smoke migration create constant risks.

Emma Lee, an expert in fire safety with years of firefighting and Rescuer experience, writes to educate on arescuer.com, sharing life-saving tips and insights.