Understanding the New Face of Sudan’s Fire Problem

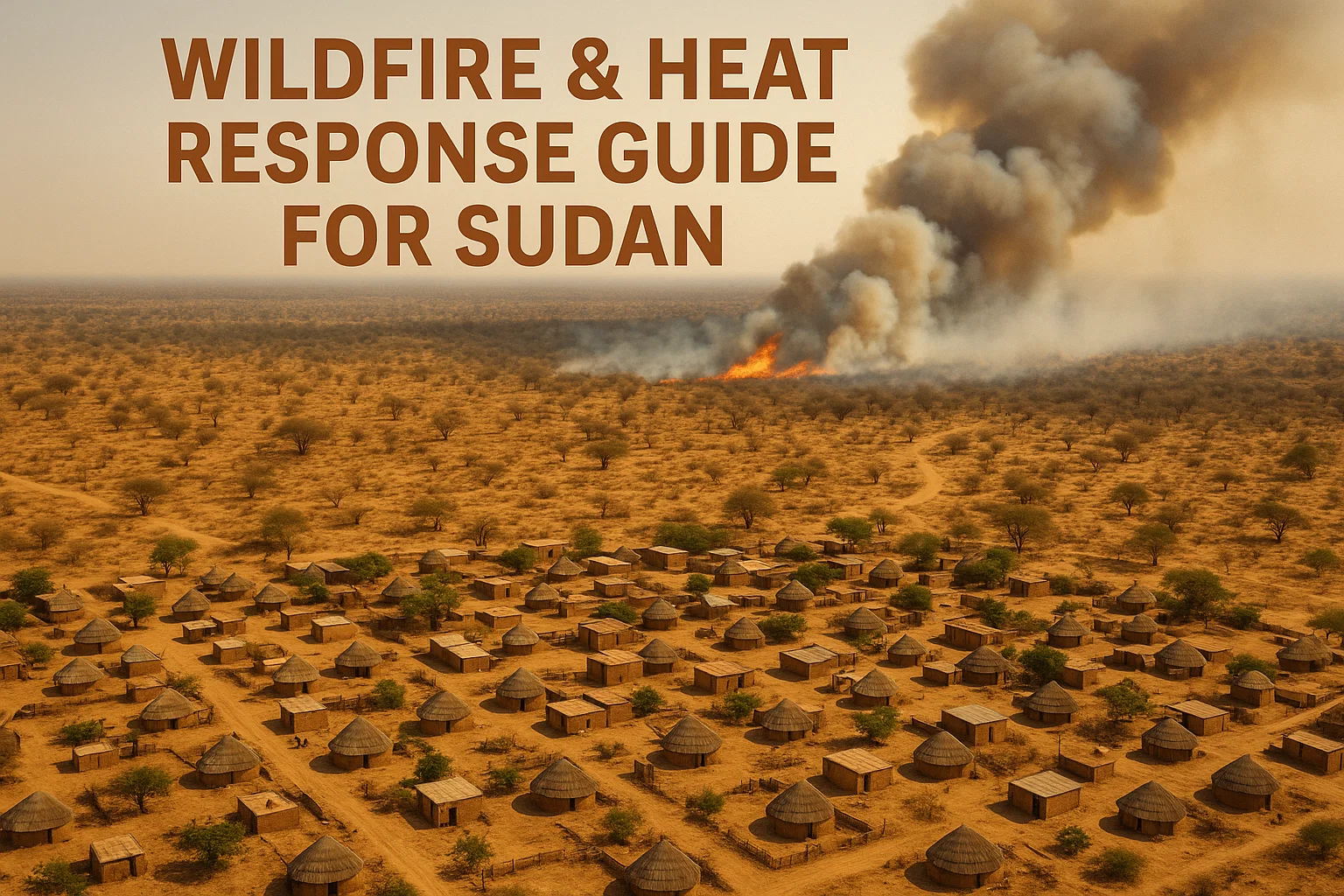

Sudan has always battled dry-season fires, but recent climate shifts have turned those events from predictable to perilous. Temperatures routinely cross 45 °C (113 °F), wind speeds climb sharply in the Harmattan season, and villages built near bushland now sit squarely in the wildland–urban interface (WUI) that thin line where nature meets human habitation.

Three factors make these fires deadlier today:

- Rising Heat Load – Continuous heatwaves dry out vegetation faster, giving fires more fuel.

- Expanding WUI Zones – Population growth and displaced settlements push further into bushland.

- Delayed Alerts & Limited Evacuation Routes – Sparse communication networks hinder early action.

Field Reality: When Heat Turns Fire into Disaster

In April 2024, villages outside El Fasher, Darfur witnessed one of the most severe fire episodes in recent memory. Local volunteers and civil defense officers reported that flames, driven by 40 km/h winds, crossed two kilometers of grassland in less than 12 minutes. The heat index hit 50 °C, making firefighting almost impossible after midday.

Many communities received warnings only when smoke was already visible. Without public-alert sirens or reliable cellular coverage, residents relied on word-of-mouth or mosque loudspeakers to coordinate escape.

These incidents highlight the gap between climate adaptation policies and field-level preparedness.

How Heat Waves Amplify WUI Fire Behavior

At first glance, a heatwave and a wildfire may seem like separate threats one atmospheric, one terrestrial. In reality, they are mutually reinforcing hazards.

- Thermal Updrafts: Hot air over dry soil accelerates convection, feeding flames with oxygen.

- Fuel Moisture Decline: A 1 °C rise can lower vegetation moisture by up to 3 %, converting green shrubs into fire ladders.

- Radiant Heat Spread: Houses with metal roofs or gas cylinders amplify heat reflection, pre-igniting nearby fuel.

According to NIST’s WUI Fire Evacuation Framework (2023), these compound effects demand dual planning one plan for wildfire spread and another for heat-exposure sheltering.

The Human Dimension: Evacuation as a Behavioral Challenge

Evacuation isn’t just logistics; it’s psychology. In Sudan’s rural settings, families hesitate to leave livestock or homes, especially when trust in authorities is thin.

Community educators often find that:

- People underestimate wind-driven fire speed.

- Heat exhaustion limits mobility, especially among elders.

- Social cohesion can delay decision-making families wait for each other before moving.

Pro Tip (from field experience):

Always identify one “safety leader” per cluster of households someone trained to recognize cues and trigger movement when alerts sound.

Building a Reliable Public-Alert System

For a WUI evacuation to work, time and trust must align. Sudan’s current early-warning ecosystem relies on a mix of meteorological updates, radio bulletins, and local leadership communication.

A practical alert chain can look like this:

| Alert Stage | Trigger Condition | Communication Mode | Lead Authority |

|---|---|---|---|

| Watch | Fire danger index > 30 | SMS / FM Radio | Sudan Meteorological Authority |

| Warning | Confirmed fire < 10 km from settlement | Mosque loudspeaker / Community bell | Civil Defense |

| Evacuate | Fire < 3 km or heavy smoke detected | Vehicle siren + megaphone + door-to-door call | Local Volunteers |

| All Clear | Fire perimeter secured | Radio / Mobile notice | Incident Command Center |

Integrating these with UHF/VHF radios for responders and WhatsApp-based micro-alerts for youth volunteers can significantly reduce lag time.

Engineering Safer Settlements in the WUI

Physical design is just as vital as communication. Sudanese engineers and NGOs working on reconstruction after conflict can incorporate fire-resistant layouts:

- Maintain 30-meter vegetation clearance around homes.

- Use mud-brick or cement walls instead of timber.

- Create community fire breaks five-meter-wide strips cleared of shrubs.

- Equip every cluster with 200-liter water drums for initial suppression.

These measures comply with NFPA 1144: Standard for Reducing Structure Ignition Hazards from Wildland Fire, adapted for local materials.

Training Emergency Services for Heat + Fire Response

Frontline teams in Sudan often face hydration stress and equipment failure in peak heat. A typical 4-hour deployment in 45 °C requires at least 1 liter of water per responder per 30 minutes.

Checklist: Heat-Aware Firefighting Deployment

- Pre-assign rest rotation (15 min per hour in shade)

- Carry electrolyte sachets in every tender

- Use wet towels under helmets to prevent heatstroke

- Monitor heart rate; > 140 bpm = mandatory cooldown

- Never stage vehicles on dry grass tire ignition risk

These micro-protocols mirror WHO occupational heat guidelines but are adapted for fireground conditions.

Case Study: Darfur WUI Evacuation Drill 2025

In early 2025, the Sudan Civil Defense ran a pilot drill simulating wildfire encroachment on a peri-urban zone outside Nyala. The operation involved 120 participants, including volunteers, schoolteachers, and Red Crescent teams.

Findings:

- Evacuation time improved by 38 % when using combined radio + WhatsApp alerts.

- Families moved faster when livestock pens had pre-designated drop-gates.

- Women leaders proved essential in mobilizing children and elders.

Such drills illustrate that preparedness is not a luxury it’s an equalizer when national firefighting capacity is thin.

Public Awareness: Turning Education into Protection

The most advanced alert system fails if citizens don’t understand its signals. Continuous public campaigns can bridge that gap:

- School Fire-Safety Days – simple WUI escape maps for children.

- Market Outreach Booths – posters showing “Ready-Set-Go” evacuation steps.

- Local Radio Segments – 60-second tips on fire season behavior.

Pro Tip:

Pair every awareness event with real-world action distribute reflective tapes for homes or conduct a five-minute smoke drill. It turns knowledge into habit.

Integrating Regional & International Frameworks

Sudan can learn from the African Union Disaster Risk Reduction Strategy (2022-2032) and FAO’s Fire Management Strategy for Sudan (2023). Both emphasize:

- Cross-border coordination (fires in Chad or Eritrea can drift across).

- Community fire brigades with micro-funding for local equipment.

- Satellite-based early-warning via NASA’s FIRMS system to monitor hotspots.

These tools allow local authorities to detect ignition early, issue alerts faster, and plan evacuation corridors using open-source mapping.

Table – Key Heat & Wildfire Response Parameters

| Parameter | Recommended Limit | Operational Note |

|---|---|---|

| Air Temp > 43 °C | Suspend day-shift beyond 2 hours | Heatstroke risk escalates |

| Relative Humidity < 20 % | Red Flag condition | Fuel moisture < 6 % |

| Wind > 30 km/h | Alert Level 3 (Immediate Watch) | Spotting likely |

| Fireline Intensity > 2,000 kW/m | Evacuation Trigger | Flame length > 3 m |

| PM2.5 > 150 µg/m³ | Respiratory Hazard | Use N95 masks or cloth filters |

These figures integrate FAO field guidelines and NFPA WUI standards.

Building a Future-Ready Sudanese Alert Model

A sustainable system blends technology, tradition, and trust. Sudan’s social structure favors communal action a strength that modern alert design can leverage.

Recommended approach:

- Integrate village leaders into the formal alert network.

- Deploy solar-powered sirens in WUI clusters.

- Adopt mobile-first micro-alerts using local dialects.

- Establish Incident Command Centers in each state capital with ICS-trained staff.

Pro Tip:

Run joint simulations during cooler months. Every minute saved in planning saves lives in the heat of June.

Lessons for Emergency Services

- WUI fires are no longer rare they are annual realities.

- Heatwave synergy demands dual planning: evacuation + heat sheltering.

- Community trust defines evacuation success.

- Local adaptation of global frameworks ensures continuity despite limited budgets.

Frequently Asked Questions

Q 1: What does “WUI” mean for Sudan?

It refers to zones where wild vegetation meets human structures common around villages expanding into dry savanna.

Q 2: How can public alerts reach remote communities without internet?

By combining mosque loudspeakers, FM radio, solar sirens, and volunteer couriers a layered communication model.

Q 3: Why is heat such a major factor?

Extreme heat pre-dries vegetation, weakens responders, and intensifies fire spread. It turns a controllable blaze into a fast-moving inferno.

Q 4: Which global standards guide Sudan’s wildfire planning?

NFPA 1144, NFPA 1600, NIST WUI Evacuation Guide, FAO Fire Management Strategy for Sudan (2023), and WHO Heat Stress Protocols.

Q 5: What’s the single most important community action?

Establish a neighborhood alert leader network simple, cheap, and proven to cut response time dramatically.

Emma Lee, an expert in fire safety with years of firefighting and Rescuer experience, writes to educate on arescuer.com, sharing life-saving tips and insights.